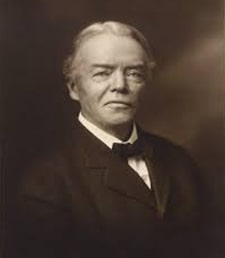

Josiah Royce (1855-1916) was a leading American proponent of absolute idealism, the metaphysical belief that all aspects of reality, including those we experience as disconnected or contradictory, are ultimately united in the thought of a single, all-encompassing consciousness. Royce also made original contributions to ethics, the philosophy of society, the philosophy of religion, and logic.

His major works include books on religious philosophy, world and individual theory, and a critique of Christianity. Royce’s friendly but longstanding dispute with William James, known as the “Battle for the Absolute”, deeply influenced the thought of both philosophers. In his later works, Royce reconceived his metaphysics as an “absolute pragmatism” based on semiotics.

Royce was born in the small mining town of Grass Valley, California. Royce’s mother and older sisters supervised his early education. When he was eleven, he started attending school in San Francisco. He graduated from the newly established University of California, Oakland with a Bachelor’s degree. He earned his degree in Classics from the University of Michigan in 1875. Royce then traveled to Germany to study philosophy for a year, mastering the language and attending lectures in Heidelberg, Leipzig, and Gottingen. Upon his return, he entered the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, where he earned a PhD. During this time, he published a number of philosophical articles and his Primer of Logical Analysis.

In January 1883, he came to the realization that in order for our ordinary concepts of truth and error to be meaningful, there must be an actual infinite mind that encompasses the totality of all actual truths and all possible errors. The insight that formed the core of his first major philosophical publication, The Religious Aspect of Philosophy, was that the nature of religious experiences is a matter of subjective interpretation. Royce was appointed as an assistant professor at Harvard in the same year he received his permanent appointment.

He was a full-time professor and gave many public lectures, as well as publishing his History of California in 1886 and a novel in 1887. In 1888, he experienced a nervous breakdown that lasted for a few months. After a sea voyage of some months, he recovered.

Later, Royce was appointed professor of the history of philosophy at Harvard in 1892 and served as chair of the department from 1894-98. During these years, Royce established himself as a leading figure in American academic philosophy with his numerous reviews, lectures, and books, including The Spirit of Modern Philosophy (1892) and The Conception of God (1895). In 1898, Royce attended a series of lectures by Charles S. Peirce, “Reasoning and the Logic of Things,” which had a significant impact on his understanding of the relationship between logic and metaphysics. He was excited about the opportunity to consolidate his years of hard work and study into one definitive statement of his metaphysics. The result of his two-volume opus, The World and the Individual (1899-1901), was his work.

The Philosophy of Loyalty, a major work on ethics, was published in 1908. Later he approached ethics in more practical terms, not as a philosophy, but as the “art” of loyalty. He published two collections of essays on race, provincialism, and other American problems in 1908 and 1911. Four of the six “Hopes of a Great Community” essays written in the last year of his life and published posthumously in 1916 dealt directly with world politics and the Great War.

Although Royce lived only a few years after his philosophical breakthrough, his last period brought the true climax and flourishing of his life’s business. There are a number of noteworthy works that can be found on religion, including The Sources of Religious Insight and The Problem of Christianity. Additionally, his last Harvard seminar on Metaphysics (1915-16) and several lectures are worth mentioning.

Royce died on September 14, 1916. Although scholars now recognize the originality and strength of his latest work, he has been unable to respond to critics or defend his case for the latest important innovations in his philosophy.